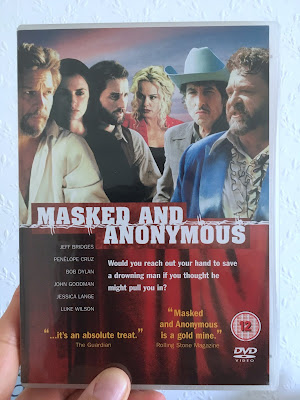

An awkward, over-stylised mess. The “plot”, what there is of one, details a future North America in which society has partly broken down. An iconic rock star named Jack Fate (Bob Dylan) is released from prison to play a benefit concert.

There are too many actors. None of them have much to do but they all look a little too pleased with themselves for being in a film with Bob Dylan. As usual, John Goodman plays an annoying fat crook. I find him unbearable – exactly the same persona in every role. Jeff Bridges plays a journalist and Penélope Cruz is his strange girlfriend. These characters have the annoying names Uncle Sweetheart, Tom Friend and Pagan Lace.

The all-star cast also includes Jessica Lange, Luke Wilson, Val Kilmer, Chris Penn, Mickey Rourke and Christian Slater. It’s remarkable that you end up not caring about a single character, as none of them are remotely developed. They are all merely mouthpieces for self-consciously cryptic speeches and pseudo-profound utterances that add up to very little. Even Bob Dylan gets annoying, and he was the only reason I watched the film. Yes, he’s enigmatic and charismatic – he can’t be anything else – but nothing is ever done with those qualities.

The music is the most interesting element: Dylan performs a few songs “live” within the film and every other song featured on the soundtrack was written by him but performed by another musician.

The political angle is another missed opportunity. We learn that totalitarianism is bad.

I found it difficult to get to the end, but I ploughed on out of misplaced loyalty to Bob.